Once upon a time, a knight by the name of Sir Henry built himself a castle. It was magnificent and kitschy and big. So big, in fact, that it was the biggest home anyone had ever built for themselves in the whole history of Canada. It had 98 rooms. 30 bathrooms. 25 fireplaces. An elevator and a central vacuum system and space for an indoor swimming pool. An oven so big you could cook an entire cow in it. A library with thousands of books. Plus stables, secret passages, a tunnel, a fountain, a shooting gallery and three bowling alleys. It had been built by 300 construction workers at a cost of millions of dollars over the course of three years. And it was all made possible because Sir Henry Pellatt wasn't just a knight, he was also one of the richest and most powerful businessmen in the country. And one of the most famously crooked, too.

Dude was very 1%. Sir Henry's dad had been one of the most powerful stock brokers in Canada. And when he retired in the late 1800s, his son inherited the business. By then, Pellatt was already an extremely well-connected young man. He'd gone to Upper Canada College, made a name for himself as a teenager by setting the world record for running the mile (!!!), and joined the prestigious Queen's Own Rifles military regiment. Plus, he was a member of all the most important gentlemen's clubs — including the Albany Club on King Street: the official Conservative party hangout.

Armed with his contacts and his dad's business, Pellatt built an even bigger fortune. He invested heavily in stocks for the Canadian West, made money off the railroads, and got interested in electricity just as Edison and Tesla were about to change the world. By the time he was 30, Pellatt had a monopoly on all of the electric streetlights in Toronto. And if he had his way, that was just going to be the beginning. When he and a couple of other businessmen built the first hydroelectric dam on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, it looked like they were going to have a monopoly on all of the hydroelectric power in Ontario for a long, long time to come.

As the 1800s turned into the 1900s, Pellatt had a fortune of $17 million dollars. Which was a hell of a lot back in those days. He was the head of more than twenty companies and was on the board of a hundred more. He was listed as one of 23 men who controlled the entire Canadian economy. Some people say he controlled a quarter of it himself.

But he was also pretty crooked. He lied to his investors, lied to his creditors, lied to the Board of Directors of his own companies. He cooked books. Committed fraud. Claimed nonexistent profits. He pulled all sorts of shady tricks to artificially inflate the value of his investments. When the federal government launched a Royal Commission to investigate this kind of stuff in the life insurance industry, Pellatt was specifically singled out for his sketchiness. When his father died, Pellatt even took money from the inheritance of his own siblings.

One day, his lies would catch up with him. And when they did, he would take the savings of thousands of innocent people and one of Canada's biggest banks with him. But until then, he was going to spend money like crazy. He bought all the fanciest new stuff, collected art and horses and cars. He had a beautiful home on Sherbourne and a country estate north of the city. He gave generously to the charities he believed in and even helped organize the first Canadian chapter of St. John's Ambulance.

But Pellatt especially liked to lavish money on his favourite militia. He eventually became commander of the Queen's Own Rifles and for the regiment's 50th anniversary, he threw a MASSIVE week-long party at the Ex. Every night there was a two-hour spectacle celebrating the military history of Canada: 1200 performers, two military bands, huge sets and elaborate costumes. Ten thousand people came to see it. Pellatt's wife, Lady Mary, presided over the festivities in diamonds and rubies and a gold crown.

And that wasn't all. A few years later, as the First World War approached, Pellatt took the entire 650-man regiment to England for military maneuvers. He paid for the whole thing himself — even brought all the horses along — and took great pride in showing the English that the Canadian military was willing and able to fight for the Empire.

The trip to England and the show at the Ex were both hailed as great successes (although a couple of people did die: one soldier — Peter Gzowski's great-uncle, oddly enough — was killed by typhoid while the regiment was in England, and one of the actors in the show was impaled on the pommel of his saddle when his horse rolled over on him). During the trip, Pellatt even got to meet the future King George V at Balmoral Castle. It was one of the greatest moments of his life.

Pellatt, like any good old-timey Canadian Conservative, was a big fan of the monarchy. When Queen Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee, Pellatt went to England with some of the Queen's Own Rifles to be part of the honour guard. He even got a signed photo. When King George was crowned, not only did Pellatt go, they say he had a commemorative medal made for pretty much every child in Toronto. And that was nothing: in 1905, he talked his contacts into getting him knighted. One day, Sir Henry dreamed, he would be given a hereditary title to pass down to his son — and the Pellatt family would officially join the ranks of the British Empire's aristocracy.

And like any good old-timey British aristocrat, Sir Henry wanted to live in a castle.

He bought himself some of the most prestigious land in the city: everything from Davenport up to St. Clair and from Bathurst to Spadina, where Toronto's oldest ruling families had once built their country estates on the hill overlooking the city. Pellatt developed part of the land as housing, but kept the rest for his castle. To build it, he hired Toronto's grandest architect: E.J. Lennox, the same guy who designed Old City Hall, the King Edward Hotel, and the west wing of Queen's Park. Lennox came up with a design that combined Pellatt's favourite elements from his favourite castles — a medieval pastiche of architectural ideas from all over Europe, especially from Balmoral, the British monarchy's summer home in Scotland where Pellatt had met King George. And to top it all off, Sir Henry gave his castle a Spanish name: Casa Loma, the house on the hill.

Pellatt hoped to host royalty at his new home, so he wasn't going to spare any expense. Masons were shipped in from the Old World; stones for the wall were hand-picked by Lennox himself. Wood was ordered from all over the globe and carved by master craftsmen. Even the horses' stalls in the stables were made of mahogany, the floors of Spanish tile. The fixtures in the bathrooms were gold. The lighting and telephone systems were state of the art. The gardens and greenhouses were filled with rare and exotic flowers. The Simpson's department store was hired to find all of the most lavish art, furniture, wine and treasure — Pellatt wanted to quickly assemble the kind of historic collection those old, British, Downton Abbey-type families had built over the course of a few centuries. And he was willing to pay millions of dollars to do it.

Of course, not everyone in Toronto was that lucky corrupt savvy at business. There was plenty of poverty in the city. Just a couple of kilometers away, at the foot of Casa Loma's hill, people were living in tar paper shacks. And in the distance, in the shadow of the spire of Old City Hall (which Pellatt could see from his window), poor immigrant families were squeezed together in the squalor of The Ward — a slum that used to be where Nathan Phillips Square is now. Slumlords forced tenants into overcrowded, ramshackle housing, rife with disease. Many families still lived without running water or even a drain. Those lucky enough to find work were likely to be working painfully long hours for low wages at dangerous factory jobs, in a city thick with coal smoke.

So, as you might expect, income disparity was a really big issue during the twenty years that Pellatt was planning and building and living in Casa Loma. Newspaper headlines were full of stories about injustice and of the clashes between the working and ruling classes. The Titanic sank with poor passengers left to drown. The Bolshevik Revolution brought Communism to Russia. The trenches of the First World War made a mockery of class distinctions. Meanwhile, unions were getting stronger and more powerful than ever, demanding stuff like a minimum wage, safer working conditions and an 8-hour workday. They were denounced as radicals, sometimes beaten by the police, even killed. In Winnipeg, when workers put together the biggest general strike in Canadian history, Mounties charged into the crowd on horseback, swinging clubs and firing their guns. Two strikers were killed and hundreds more were injured. They called it Bloody Saturday.

Sir Henry was no stranger to the violent side of labour relations. The only time he ever saw action with the Queen's Own Rifles was back in his younger days when they were called in to break a railway strike in Belleville. The regiment advanced on the workers with their bayonets drawn. Two strikers were stabbed and two soldiers were hit in the head by flying rocks. After it was all over, the men of the QOR were presented with medals made out of the rails the workers had pulled up. Pellatt wore his on his dress uniform for the rest of his life.

It wouldn't be the last time Sir Henry got caught up in the debate over private profit and the public interest. In fact, he played a central role in one of the biggest fights about it that our city has ever seen.

This was back before he started building Casa Loma. And it was about that hydroelectric dam he and his friends were building at Niagara Falls. It was a big deal: an engineering marvel, a beautiful design by E.J. Lennox, and a whole crapload of money-making potential. But at the same time the dam was being built, the public was getting fed up with private monopolies. The government didn't provide a lot of the public services it does today — and the private companies who did provide them had a reputation for using their monopolies to drive up prices while letting the quality of the services plummet.

As The Globe put it in the year 1900: "the twentieth century will be kept busy wrestling with millionaires and billionaires to get back and restore to the people that which the nineteenth century gave away... The nineteenth century shirked its duty, humbugged and defrauded the common people, playing into the hands of the rich..."

And so, many were beginning to suggest that hydroelectric power should belong to the people, not to Pellatt's private corporation. The champion of the idea was Adam Beck, the former Mayor of London who was now a Conservative MPP. "The gifts of nature are for the public," he declared. And he pushed the Conservative government to agree. "It is the duty of the Government to see that development is not hindered by permitting a handful of people to enrich themselves out of these treasures at the expense of the general public."

While Beck was leading the charge at Queen's Park, a man named William Peyton Hubbard was doing the same thing a couple of blocks down the street at City Hall. He was the son of escaped slaves, and had gotten into politics after saving George Brown from drowning in the Don River. He became the city's first Black alderman — the first Black politician elected in any Canadian city — and he sat on Toronto's City Council for a couple of decades, even stepping in as acting mayor more than once. He and Beck both argued in favour of what they called "public power."

Pellatt and his friends fought back. They claimed Beck's idea was the worst kind of socialism. That since they'd built the dam, they should profit from it. And that British investors would be scared away. (They then tried to get the British investors to promise that they would be scared away.) Pellatt even asked King Edward VII to intervene — but without any luck. The businessmen were eventually so desperate that they tried to bribe one of the newspapers who opposed them: $350,000 if the Toronto World switched sides and started arguing against public power. It didn't work.

None of it worked. The Conservative government at Queen's Park agreed with Beck. Premier James Whitney got up in the legislature and declared that "water-power at Niagara should be as free as air and, more than that, I say on behalf of the Government that the water-power all over this country shall not in future be made the sport and prey of capitalists, and shall not be treated as anything else, but as a valuable asset of the people of Ontario".

That's how Ontario Hydro was founded. It became the biggest publicly-owned corporation on the continent. (It would survive all the way to the 1990s — until Mike Harris split it into

pieces and sold some of them off to private owners.) Eventually, the government would take over the company Pellatt and his friends had founded for more than $30 million. And with William Peyton Hubbard leading the way, Toronto soon signed on to the new public power grid with a dazzling ceremony at Old City Hall.

Beck was knighted for his public service. And Toronto City Council built a monument in his honour. It's still there today: a bronze statue in the middle of University Avenue just south of Queen. In the years that followed, City Hall would take on more and more of the public services that private companies had been providing — it was even one of Pellatt's hydroelectric partners who lost the streetcar contract, allowing the city to create the TTC.

When people talk about how Sir Henry lost his fortune, they tend to mention that whole public power episode quite a bit. But he actually seems to have recovered pretty easily from it. He was still one of the most extravagantly wealthy men in the country. And he would be for a while. He started construction on Casa Loma soon after, and he lived there for a decade before everything fell apart. He and Lady Mary turned it into a social hub. They threw some of the most lavish parties in our city's history: garden parties, curling parties, hockey parties, diners with a hundred guests. And they threw parties for their favourite public causes, too. The Queen's Own Rifles were regular guests. And so were the Girl Guides of Canada — Lady Mary had been drafted into being their first Chief Commissioner (in part because she was super-rich and influential, in part because of her traditional views on womanhood and the vote). Pellatt would even fulfill his dream of hosting royalty: The Prince of Wales, who would go on to briefly become King Edward VIII before he abdicated his throne and left it to his stuttering brother, visited Casa Loma not just once, but twice.

Pellatt wasn't done fighting with the government, either. The feds took over his airplane factory during WWI. And when the Wall Street Journal accused him of making an exorbitant profit while selling shells to the army during the war, the Prime Minister forced Sir Henry to make a public denial. He waged a battle with the city over his property taxes, too. They'd gone up after he built his castle, so he took the city to court. His lawyers argued that Casa Loma was so big and so expensive that it actually drove the value of the property down — that Pellatt was a fool to have built it. (Meanwhile, he'd already mortgaged it for four times what the city claimed it was worth.)

Still, it wasn't until 1923 that everything finally went to shit. Here's how it happened:

Pellatt had borrowed a lot of money from a lot of different people. One of them was the Home Bank of Canada. It had been founded in Toronto back in the 1850s by our city's second Catholic Bishop. The idea was that it would give poor Irish-Catholic immigrant families a place to invest and get loans in super-Protestant, Catholic-hating Toronto. But over the course of time, the bank had become more and more secular, less and less charitable, and more just like a regular bank. Now, it had branches all over the country — more than 80 of them (including one on King Street just west of Yonge designed in part by E.J. Lennox). Tens of thousands of working class people had put their savings into the bank, Toronto Catholics and farmers in the Prairies more than anybody else.

Sir Henry, on the other hand, was in the habit of taking money out of the bank. It was run by a couple of friends of his: a Conservative Senator and his son, both of them from the Queen's Own Rifles. They were pretty sketchy business-wise, happy to lend their customers' money out to their friends without making sure those friends could pay it back. They gave Pellatt more money than anybody else, millions and millions of dollars, cooking their books to back some of his dubious investments. In return, they were supposed to get a cut of his profits.

But those profits never came. Pellatt was pulling his usual shady tricks, and this time they weren't going to work.

For instance: He used a lot of the money to buy a bunch of land, sort north-west of Bathurst and St. Clair. Then, he sold that land to himself at an inflated price. That way, he could use the inflated value of the land as collateral to borrow even more money to buy even more land. But when the First World War broke out, people stopped buying land. And when it ended, the economy didn't recover right away. So when the bank was finally forced to ask Pellatt to pay them back, he just couldn't. All he had was a bunch of land and stocks that weren't worth anything near what he claimed they were worth. Plus, a giant castle and a shit load of debt. He owed the Home Bank $2 million and that was just one debt of many. He was screwed. And so was the Home Bank.

Pellatt desperately schemed and stalled and skimmed money — even dumped some of his sketchiest stocks on the staff at Casa Loma — begging for more time, but eventually that time ran out. The fraud was uncovered. On a Saturday morning in the summer of 1923, a blunt notice was hammered into the beautiful wooden door of the Home Bank branch on King Street: "BANK CLOSED PAYMENT SUSPENDED".

And just like that, everyone's money was gone.

Tens of thousands of Canadians lost their life savings. One customer even died of a heart attack at a public meeting about it at Massey Hall. Ten bank officials were arrested. One had a nervous breakdown. Some people say the Senator's son — who had once survived an armed bank robbery and a bullet through his lungs during the Great Boer War — killed himself because of it. Wikipedia goes as far as to link the bank's collapse with the rise of populist political parties out West — farmers on the Prairies were pretty pissed off at the Eastern bankers who had screwed them over.

In the end, the federal government, now run by Mackenzie King's Liberals, launched a Royal Commission to investigate the collapse. Corruption was uncovered. New rules were proposed. Conservative ministers from the previous government were grilled about a suspicious bailout they'd given the bank. Eventually, laws were changed to outlaw some of Pellatt's dirtiest tricks. And a new "Inspector General of Banks" was appointed to make sure those new laws were obeyed. About ten years later, on top of all the new regulations, the Bank of Canada was created to help control the country's banking system. Not a single Canadian bank has failed since.

Pellatt, meanwhile, managed to cover his own ass — but only legally. Before the collapse, he moved his assets around so he could never be sued for it. And he put Casa Loma in his wife's name so it couldn't be seized. His days as a titan of industry were over, though. His fortune was gone; his reputation ruined.

And so, Sir Henry was forced to move out of Casa Loma. The castle was waaaaaay too expensive to run: it took a million and a half pounds of coal to heat it every winter and tens of thousands of dollars to keep it staffed. He and Lady Mary moved into an apartment on Spadina, but she died soon after that — of a broken heart, they like to say. It was downhill from there. Pellatt remarried, but when his new wife died of cancer he bitterly accused her of having known she was sick all along — that she'd "bamboozled" him into marrying her. He moved into one smaller apartment after another. And when the Great Depression struck, Pellatt couldn't afford the castle's property taxes anymore. Ten years after the Home Bank collapsed, the City of Toronto took over Casa Loma.

Sir Henry was an old man by then. The last photos of him are pretty sad. He was thin and frail, almost blind from cataracts. He walked with a cane. He doesn't look anything like the imposing figure who spent 40 years as a financial giant. He looks like a tired old man. Defeated. And very mortal.

He spent his final days living with his chauffeur's family at their home in Mimico, down by the lake in the west end. He didn't have many friends or family left to care for him, but his niece and her mother would come by to read to him and listen to his stories. He consoled himself by retelling tales from the old days and with the few mementos he had left: his signed photo of Queen Victoria, his invitation to King George's coronation, a seating plan for the dinner at Balmoral... He still had his knighthood too — the city hadn't forced him to formally declare bankruptcy, so he got to keep it. And there was one last fancy dinner at the Royal York Hotel: a reunion of the Queen's Own Rifles for his 80th birthday, including a telegram of congratulations from King George's wife Queen Mary. Sir Henry was moved to tears. He died two months later, in his chauffeur's arms.

The Queen's Own Rifles gave him a full military funeral at St. James Cathedral, on the spot where Toronto has said goodbye to its most powerful Anglicans for more than 200 years. Thousands of people came to pay their respects.

Meanwhile, Casa Loma, once a monument to private wealth, was now in public hands. And it was quite the handful.

For ten years after the Pellatts moved out, the castle had been pretty much abandoned. It was a wreck. Kids had chucked rocks through all the windows; there were thousands of panes of broken glass. The pipes had frozen and burst, which let water warp the hardwood floors and the wood-paneled walls. Hundreds of birds and animals had moved in: owls and pigeons and bats. The floors were covered with layers of bird shit and bat shit and garbage and dirt and ashes and leaves. Restoring Casa Loma was going to be a major project. And plenty of people didn't think it was worth it — especially in the middle of the Great Depression. In fact, the very same year the city took over the castle, the Liberals won the provincial election with a promise to shut down Toronto's other grandest home: Chorley Park, the Lieutenant Governor's spectacular residence in Rosedale. Even just keeping the thing heated, they argued, was an extravagant waste of the taxpayers' money.

For a while the city thought about just tearing Casa Loma down. Or burning it down. Or blowing it up. But even that was going to be a ridiculous and expensive ordeal. It was a castle: so incredibly big and so incredibly well-built that an explosion big enough to knock it down would also destroy the surrounding houses and shatter every window in the west end.

There were plenty of other ideas, though. Pellatt had already briefly let it be turned into a nightclub. (The Casa Loma Orchestra became one of the biggest swing bands of the '30s.) E.J. Lennox figured he could turn it into an apartment building. Mary Pickford wondered about using it as a movie studio. Some people said it should be a gentlemen's club or an Orange Lodge or a monastery. Even a residence for the Pope. Or for the King. Others suggested that it should turned into a subway station or a fancy morgue or a home for the Dionne quintuplets — that same Liberal provincial government was in the process of turning the five baby sisters into the biggest tourist draw in Ontario.

But in the end, City Council decided to let the Kiwanis Club run Casa Loma as a tourist attraction in its own right. They cleared out truckloads of filth, repaired all the damage, even finished parts of the castle that Pellatt had never been able to. And then they opened Toronto's most lavish private residence to the public. For 25 cents, you could wander through the castle, climb the tower, slip through secret passages and stroll through the gardens, walk the long tunnel to the stables, and wonder what it must have been like to be that rich.

The Kiwanis Club has been running Casa Loma ever since. And for the most part, those 75 years have passed without incident — even while the army was using the stables as a secret base to build a new SONAR system during the Second World War.

But recently, things haven't been going so well. For one thing, as awesome as the castle is (and it's pretty awesome) there's not much to see beyond the building itself. Back when the Pellatts were forced to move out, their historic collection of art and artifacts was sold off. It took five days to auction it all — most pieces sold for a tiny fraction of what they were actually worth. Chippendale and Louis XVI and Elizabethan furniture was bought at bargain basement prices. Chairs from the 1600s went for $30 each. Lady Mary's bedroom set from the 1700s went for $45. A brand new $75,000 pipe organ was bought for 40 bucks. There were paintings by Turner and Van Dyke and Paul Peel. A china set they say Napoleon presented to one of his generals. Even some Toronto history: a water bottle that once belonged to the man who founded our city, John Graves Simcoe.

So today, Casa Loma is little more than an Henry Pellatt Museum — without most of the stuff Sir Henry Pellatt actually owned. Some of the rooms are filled with period pieces. A few are dedicated to the history of the Queen's Own Rifles. There's a Girl Guides display. There's even a room dedicated to dispelling the "myths" of Pellatt's corruption (and a short video, too, narrated by Colin Mochrie), which conveniently skips over his lies and fraud, implying that his failure had much more to do with Adam Beck and the government than anything Sir Henry did.

Meanwhile, the castle has fallen into disrepair. Millions of dollars are needed to fix it up — costs the Kiwanis Club says they just can't afford. These days, the walls of the tower and the tunnel are tagged with graffiti, some of which clearly hasn't been cleaned up for years.

So it's not all that surprising to hear that attendance has been falling. Especially when you consider that admission is now about $20 — way more than Toronto's other historic sites. Fort York is less than $8. Mackenzie House is about $6. This month, you can go see "A Christmas Carol" at Montgomery's Inn for $15. And then there's Spadina House: also filled with period pieces, with an admission price less than half of Casa Loma's, and it's right next door to the castle.

When David Miller renewed the Kiwanis Club's contract back when he was Mayor, he almost immediately regretted it. (On top of everything else, Miller claimed the Casa Loma board was giving their own Chair all of the castle's legal work — that he made hundreds of thousands of dollars while the castle deteriorated.) So Miller bought out the Club. And now, 80 years after the city first seized it, the castle on the hill is back in Toronto's hands.

There are again plenty of ideas for how the castle should be used this time around. Rob Ford, unsurprisingly, argued that the city would have to sell it off to private interests. Some want it turned into condos. Or a hotel. There's even a Facebook group asking Drake to buy it and turn it into Casa YOLO.

But with Council's backing, two City Councillors hope they've found a new public use for it. Josh Matlow and Joe Mihevc are asking that part of Casa Loma be turned into a Toronto Museum. Instead of being a monument to the history of one man, it would be a monument to the entire history of our city. Once home to Pellatt's private collection, the castle would now be home to some of the more than 100,000 historic artifacts in the city's collection. The vast majority of them have been sitting in storage, out of public view, waiting for a chance to tell Toronto's story.

That's all assuming, of course, that everything goes well. It won't be easy. Or cheap. The city has been actively trying to find a home for a Toronto Museum for nearly a decade now — first at the Canada Malting silos on the waterfont and then at Old City Hall — without any luck. And no one even knows who the Mayor's going to be a few weeks from now. But they've already started public consultations. And later this month, a Request for Proposal will be sent out, asking for the castle to be used as "an historic attraction and special event venue" with the Toronto Museum as part of the plans.

So maybe, just maybe, after nearly a century spent looking out over the city from that hill above Davenport, after all of those ups and downs — the swanky parties, the tragic neglect, the scandals and the financial collapse — Sir Henry's castle will finally have its happy ending. And if we're lucky, if it all comes together and it's all run by the right people, maybe it will be a happy ending not just for one man, or one family, or one company, but for the entire city of Toronto.

You can read Matlow and Mihevc's letter about their hopes for a Toronto Museum here. And a Toronto Star editorial in support of the idea here. There's a record of the first public consultation meeting in a PDF here. And you'll find the Agenda Item History for the Council motions about the castle here.

You can listen to The Casa Loma Orchestra play "The Casa Loma Stomp" here.

I wrote a whole big post about that Senator's son, J. Cooper Mason, who survived the armed bank robbery and the Great Boer War before maybe having killed himself over the collapse of the Home Bank. You can check that out here.

I can't resist mentioning how much Sir Henry reminds me of another rotund Conservative millionaire who inherited his business from his father, likes sports, throws huge public parties, has trouble following the rules, fights passionately for the charities he works with while having trouble grasping the idea of the greater public good, and once showed in court to present a case that pretty much boiled down to him being a total fool. Pellatt, like Ford, even once tried to expand his property a bit, by taking over a sliver of adjoining parkland.

I also find Sir Henry's story an interesting compliment to Downton Abbey. He was trying to establish himself as the Canadian equivalent of that fictional family, at the same time that they were realizing that thir old world needed to change.

Bonus quote from a Sir Adam Beck speech in Kingston on Sept. 11, 1910, after the founding of Ontario Hydro: "Our work is only begun. We must deliver power at such a price that the poorest man may have electric light. There will be no more coal oil, no more gas, and I hope in the future, no more coal."

Armed with his contacts and his dad's business, Pellatt built an even bigger fortune. He invested heavily in stocks for the Canadian West, made money off the railroads, and got interested in electricity just as Edison and Tesla were about to change the world. By the time he was 30, Pellatt had a monopoly on all of the electric streetlights in Toronto. And if he had his way, that was just going to be the beginning. When he and a couple of other businessmen built the first hydroelectric dam on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, it looked like they were going to have a monopoly on all of the hydroelectric power in Ontario for a long, long time to come.

As the 1800s turned into the 1900s, Pellatt had a fortune of $17 million dollars. Which was a hell of a lot back in those days. He was the head of more than twenty companies and was on the board of a hundred more. He was listed as one of 23 men who controlled the entire Canadian economy. Some people say he controlled a quarter of it himself.

But he was also pretty crooked. He lied to his investors, lied to his creditors, lied to the Board of Directors of his own companies. He cooked books. Committed fraud. Claimed nonexistent profits. He pulled all sorts of shady tricks to artificially inflate the value of his investments. When the federal government launched a Royal Commission to investigate this kind of stuff in the life insurance industry, Pellatt was specifically singled out for his sketchiness. When his father died, Pellatt even took money from the inheritance of his own siblings.

|

| Sir Henry Pellatt |

But Pellatt especially liked to lavish money on his favourite militia. He eventually became commander of the Queen's Own Rifles and for the regiment's 50th anniversary, he threw a MASSIVE week-long party at the Ex. Every night there was a two-hour spectacle celebrating the military history of Canada: 1200 performers, two military bands, huge sets and elaborate costumes. Ten thousand people came to see it. Pellatt's wife, Lady Mary, presided over the festivities in diamonds and rubies and a gold crown.

And that wasn't all. A few years later, as the First World War approached, Pellatt took the entire 650-man regiment to England for military maneuvers. He paid for the whole thing himself — even brought all the horses along — and took great pride in showing the English that the Canadian military was willing and able to fight for the Empire.

The trip to England and the show at the Ex were both hailed as great successes (although a couple of people did die: one soldier — Peter Gzowski's great-uncle, oddly enough — was killed by typhoid while the regiment was in England, and one of the actors in the show was impaled on the pommel of his saddle when his horse rolled over on him). During the trip, Pellatt even got to meet the future King George V at Balmoral Castle. It was one of the greatest moments of his life.

Pellatt, like any good old-timey Canadian Conservative, was a big fan of the monarchy. When Queen Victoria celebrated her Diamond Jubilee, Pellatt went to England with some of the Queen's Own Rifles to be part of the honour guard. He even got a signed photo. When King George was crowned, not only did Pellatt go, they say he had a commemorative medal made for pretty much every child in Toronto. And that was nothing: in 1905, he talked his contacts into getting him knighted. One day, Sir Henry dreamed, he would be given a hereditary title to pass down to his son — and the Pellatt family would officially join the ranks of the British Empire's aristocracy.

And like any good old-timey British aristocrat, Sir Henry wanted to live in a castle.

He bought himself some of the most prestigious land in the city: everything from Davenport up to St. Clair and from Bathurst to Spadina, where Toronto's oldest ruling families had once built their country estates on the hill overlooking the city. Pellatt developed part of the land as housing, but kept the rest for his castle. To build it, he hired Toronto's grandest architect: E.J. Lennox, the same guy who designed Old City Hall, the King Edward Hotel, and the west wing of Queen's Park. Lennox came up with a design that combined Pellatt's favourite elements from his favourite castles — a medieval pastiche of architectural ideas from all over Europe, especially from Balmoral, the British monarchy's summer home in Scotland where Pellatt had met King George. And to top it all off, Sir Henry gave his castle a Spanish name: Casa Loma, the house on the hill.

Pellatt hoped to host royalty at his new home, so he wasn't going to spare any expense. Masons were shipped in from the Old World; stones for the wall were hand-picked by Lennox himself. Wood was ordered from all over the globe and carved by master craftsmen. Even the horses' stalls in the stables were made of mahogany, the floors of Spanish tile. The fixtures in the bathrooms were gold. The lighting and telephone systems were state of the art. The gardens and greenhouses were filled with rare and exotic flowers. The Simpson's department store was hired to find all of the most lavish art, furniture, wine and treasure — Pellatt wanted to quickly assemble the kind of historic collection those old, British, Downton Abbey-type families had built over the course of a few centuries. And he was willing to pay millions of dollars to do it.

|

| The Ward in 1913 |

So, as you might expect, income disparity was a really big issue during the twenty years that Pellatt was planning and building and living in Casa Loma. Newspaper headlines were full of stories about injustice and of the clashes between the working and ruling classes. The Titanic sank with poor passengers left to drown. The Bolshevik Revolution brought Communism to Russia. The trenches of the First World War made a mockery of class distinctions. Meanwhile, unions were getting stronger and more powerful than ever, demanding stuff like a minimum wage, safer working conditions and an 8-hour workday. They were denounced as radicals, sometimes beaten by the police, even killed. In Winnipeg, when workers put together the biggest general strike in Canadian history, Mounties charged into the crowd on horseback, swinging clubs and firing their guns. Two strikers were killed and hundreds more were injured. They called it Bloody Saturday.

Sir Henry was no stranger to the violent side of labour relations. The only time he ever saw action with the Queen's Own Rifles was back in his younger days when they were called in to break a railway strike in Belleville. The regiment advanced on the workers with their bayonets drawn. Two strikers were stabbed and two soldiers were hit in the head by flying rocks. After it was all over, the men of the QOR were presented with medals made out of the rails the workers had pulled up. Pellatt wore his on his dress uniform for the rest of his life.

It wouldn't be the last time Sir Henry got caught up in the debate over private profit and the public interest. In fact, he played a central role in one of the biggest fights about it that our city has ever seen.

This was back before he started building Casa Loma. And it was about that hydroelectric dam he and his friends were building at Niagara Falls. It was a big deal: an engineering marvel, a beautiful design by E.J. Lennox, and a whole crapload of money-making potential. But at the same time the dam was being built, the public was getting fed up with private monopolies. The government didn't provide a lot of the public services it does today — and the private companies who did provide them had a reputation for using their monopolies to drive up prices while letting the quality of the services plummet.

As The Globe put it in the year 1900: "the twentieth century will be kept busy wrestling with millionaires and billionaires to get back and restore to the people that which the nineteenth century gave away... The nineteenth century shirked its duty, humbugged and defrauded the common people, playing into the hands of the rich..."

And so, many were beginning to suggest that hydroelectric power should belong to the people, not to Pellatt's private corporation. The champion of the idea was Adam Beck, the former Mayor of London who was now a Conservative MPP. "The gifts of nature are for the public," he declared. And he pushed the Conservative government to agree. "It is the duty of the Government to see that development is not hindered by permitting a handful of people to enrich themselves out of these treasures at the expense of the general public."

While Beck was leading the charge at Queen's Park, a man named William Peyton Hubbard was doing the same thing a couple of blocks down the street at City Hall. He was the son of escaped slaves, and had gotten into politics after saving George Brown from drowning in the Don River. He became the city's first Black alderman — the first Black politician elected in any Canadian city — and he sat on Toronto's City Council for a couple of decades, even stepping in as acting mayor more than once. He and Beck both argued in favour of what they called "public power."

Pellatt and his friends fought back. They claimed Beck's idea was the worst kind of socialism. That since they'd built the dam, they should profit from it. And that British investors would be scared away. (They then tried to get the British investors to promise that they would be scared away.) Pellatt even asked King Edward VII to intervene — but without any luck. The businessmen were eventually so desperate that they tried to bribe one of the newspapers who opposed them: $350,000 if the Toronto World switched sides and started arguing against public power. It didn't work.

None of it worked. The Conservative government at Queen's Park agreed with Beck. Premier James Whitney got up in the legislature and declared that "water-power at Niagara should be as free as air and, more than that, I say on behalf of the Government that the water-power all over this country shall not in future be made the sport and prey of capitalists, and shall not be treated as anything else, but as a valuable asset of the people of Ontario".

|

| Old City Hall welcomes public power in 1911 |

Beck was knighted for his public service. And Toronto City Council built a monument in his honour. It's still there today: a bronze statue in the middle of University Avenue just south of Queen. In the years that followed, City Hall would take on more and more of the public services that private companies had been providing — it was even one of Pellatt's hydroelectric partners who lost the streetcar contract, allowing the city to create the TTC.

When people talk about how Sir Henry lost his fortune, they tend to mention that whole public power episode quite a bit. But he actually seems to have recovered pretty easily from it. He was still one of the most extravagantly wealthy men in the country. And he would be for a while. He started construction on Casa Loma soon after, and he lived there for a decade before everything fell apart. He and Lady Mary turned it into a social hub. They threw some of the most lavish parties in our city's history: garden parties, curling parties, hockey parties, diners with a hundred guests. And they threw parties for their favourite public causes, too. The Queen's Own Rifles were regular guests. And so were the Girl Guides of Canada — Lady Mary had been drafted into being their first Chief Commissioner (in part because she was super-rich and influential, in part because of her traditional views on womanhood and the vote). Pellatt would even fulfill his dream of hosting royalty: The Prince of Wales, who would go on to briefly become King Edward VIII before he abdicated his throne and left it to his stuttering brother, visited Casa Loma not just once, but twice.

Pellatt wasn't done fighting with the government, either. The feds took over his airplane factory during WWI. And when the Wall Street Journal accused him of making an exorbitant profit while selling shells to the army during the war, the Prime Minister forced Sir Henry to make a public denial. He waged a battle with the city over his property taxes, too. They'd gone up after he built his castle, so he took the city to court. His lawyers argued that Casa Loma was so big and so expensive that it actually drove the value of the property down — that Pellatt was a fool to have built it. (Meanwhile, he'd already mortgaged it for four times what the city claimed it was worth.)

Still, it wasn't until 1923 that everything finally went to shit. Here's how it happened:

Pellatt had borrowed a lot of money from a lot of different people. One of them was the Home Bank of Canada. It had been founded in Toronto back in the 1850s by our city's second Catholic Bishop. The idea was that it would give poor Irish-Catholic immigrant families a place to invest and get loans in super-Protestant, Catholic-hating Toronto. But over the course of time, the bank had become more and more secular, less and less charitable, and more just like a regular bank. Now, it had branches all over the country — more than 80 of them (including one on King Street just west of Yonge designed in part by E.J. Lennox). Tens of thousands of working class people had put their savings into the bank, Toronto Catholics and farmers in the Prairies more than anybody else.

Sir Henry, on the other hand, was in the habit of taking money out of the bank. It was run by a couple of friends of his: a Conservative Senator and his son, both of them from the Queen's Own Rifles. They were pretty sketchy business-wise, happy to lend their customers' money out to their friends without making sure those friends could pay it back. They gave Pellatt more money than anybody else, millions and millions of dollars, cooking their books to back some of his dubious investments. In return, they were supposed to get a cut of his profits.

But those profits never came. Pellatt was pulling his usual shady tricks, and this time they weren't going to work.

|

| The Home Bank branch on King Street |

And just like that, everyone's money was gone.

Tens of thousands of Canadians lost their life savings. One customer even died of a heart attack at a public meeting about it at Massey Hall. Ten bank officials were arrested. One had a nervous breakdown. Some people say the Senator's son — who had once survived an armed bank robbery and a bullet through his lungs during the Great Boer War — killed himself because of it. Wikipedia goes as far as to link the bank's collapse with the rise of populist political parties out West — farmers on the Prairies were pretty pissed off at the Eastern bankers who had screwed them over.

In the end, the federal government, now run by Mackenzie King's Liberals, launched a Royal Commission to investigate the collapse. Corruption was uncovered. New rules were proposed. Conservative ministers from the previous government were grilled about a suspicious bailout they'd given the bank. Eventually, laws were changed to outlaw some of Pellatt's dirtiest tricks. And a new "Inspector General of Banks" was appointed to make sure those new laws were obeyed. About ten years later, on top of all the new regulations, the Bank of Canada was created to help control the country's banking system. Not a single Canadian bank has failed since.

Pellatt, meanwhile, managed to cover his own ass — but only legally. Before the collapse, he moved his assets around so he could never be sued for it. And he put Casa Loma in his wife's name so it couldn't be seized. His days as a titan of industry were over, though. His fortune was gone; his reputation ruined.

And so, Sir Henry was forced to move out of Casa Loma. The castle was waaaaaay too expensive to run: it took a million and a half pounds of coal to heat it every winter and tens of thousands of dollars to keep it staffed. He and Lady Mary moved into an apartment on Spadina, but she died soon after that — of a broken heart, they like to say. It was downhill from there. Pellatt remarried, but when his new wife died of cancer he bitterly accused her of having known she was sick all along — that she'd "bamboozled" him into marrying her. He moved into one smaller apartment after another. And when the Great Depression struck, Pellatt couldn't afford the castle's property taxes anymore. Ten years after the Home Bank collapsed, the City of Toronto took over Casa Loma.

|

| Sir Henry signs Casa Loma's guestbook |

He spent his final days living with his chauffeur's family at their home in Mimico, down by the lake in the west end. He didn't have many friends or family left to care for him, but his niece and her mother would come by to read to him and listen to his stories. He consoled himself by retelling tales from the old days and with the few mementos he had left: his signed photo of Queen Victoria, his invitation to King George's coronation, a seating plan for the dinner at Balmoral... He still had his knighthood too — the city hadn't forced him to formally declare bankruptcy, so he got to keep it. And there was one last fancy dinner at the Royal York Hotel: a reunion of the Queen's Own Rifles for his 80th birthday, including a telegram of congratulations from King George's wife Queen Mary. Sir Henry was moved to tears. He died two months later, in his chauffeur's arms.

The Queen's Own Rifles gave him a full military funeral at St. James Cathedral, on the spot where Toronto has said goodbye to its most powerful Anglicans for more than 200 years. Thousands of people came to pay their respects.

Meanwhile, Casa Loma, once a monument to private wealth, was now in public hands. And it was quite the handful.

For ten years after the Pellatts moved out, the castle had been pretty much abandoned. It was a wreck. Kids had chucked rocks through all the windows; there were thousands of panes of broken glass. The pipes had frozen and burst, which let water warp the hardwood floors and the wood-paneled walls. Hundreds of birds and animals had moved in: owls and pigeons and bats. The floors were covered with layers of bird shit and bat shit and garbage and dirt and ashes and leaves. Restoring Casa Loma was going to be a major project. And plenty of people didn't think it was worth it — especially in the middle of the Great Depression. In fact, the very same year the city took over the castle, the Liberals won the provincial election with a promise to shut down Toronto's other grandest home: Chorley Park, the Lieutenant Governor's spectacular residence in Rosedale. Even just keeping the thing heated, they argued, was an extravagant waste of the taxpayers' money.

For a while the city thought about just tearing Casa Loma down. Or burning it down. Or blowing it up. But even that was going to be a ridiculous and expensive ordeal. It was a castle: so incredibly big and so incredibly well-built that an explosion big enough to knock it down would also destroy the surrounding houses and shatter every window in the west end.

There were plenty of other ideas, though. Pellatt had already briefly let it be turned into a nightclub. (The Casa Loma Orchestra became one of the biggest swing bands of the '30s.) E.J. Lennox figured he could turn it into an apartment building. Mary Pickford wondered about using it as a movie studio. Some people said it should be a gentlemen's club or an Orange Lodge or a monastery. Even a residence for the Pope. Or for the King. Others suggested that it should turned into a subway station or a fancy morgue or a home for the Dionne quintuplets — that same Liberal provincial government was in the process of turning the five baby sisters into the biggest tourist draw in Ontario.

|

| The dawn of the Kiwanis Era |

The Kiwanis Club has been running Casa Loma ever since. And for the most part, those 75 years have passed without incident — even while the army was using the stables as a secret base to build a new SONAR system during the Second World War.

But recently, things haven't been going so well. For one thing, as awesome as the castle is (and it's pretty awesome) there's not much to see beyond the building itself. Back when the Pellatts were forced to move out, their historic collection of art and artifacts was sold off. It took five days to auction it all — most pieces sold for a tiny fraction of what they were actually worth. Chippendale and Louis XVI and Elizabethan furniture was bought at bargain basement prices. Chairs from the 1600s went for $30 each. Lady Mary's bedroom set from the 1700s went for $45. A brand new $75,000 pipe organ was bought for 40 bucks. There were paintings by Turner and Van Dyke and Paul Peel. A china set they say Napoleon presented to one of his generals. Even some Toronto history: a water bottle that once belonged to the man who founded our city, John Graves Simcoe.

So today, Casa Loma is little more than an Henry Pellatt Museum — without most of the stuff Sir Henry Pellatt actually owned. Some of the rooms are filled with period pieces. A few are dedicated to the history of the Queen's Own Rifles. There's a Girl Guides display. There's even a room dedicated to dispelling the "myths" of Pellatt's corruption (and a short video, too, narrated by Colin Mochrie), which conveniently skips over his lies and fraud, implying that his failure had much more to do with Adam Beck and the government than anything Sir Henry did.

Meanwhile, the castle has fallen into disrepair. Millions of dollars are needed to fix it up — costs the Kiwanis Club says they just can't afford. These days, the walls of the tower and the tunnel are tagged with graffiti, some of which clearly hasn't been cleaned up for years.

So it's not all that surprising to hear that attendance has been falling. Especially when you consider that admission is now about $20 — way more than Toronto's other historic sites. Fort York is less than $8. Mackenzie House is about $6. This month, you can go see "A Christmas Carol" at Montgomery's Inn for $15. And then there's Spadina House: also filled with period pieces, with an admission price less than half of Casa Loma's, and it's right next door to the castle.

When David Miller renewed the Kiwanis Club's contract back when he was Mayor, he almost immediately regretted it. (On top of everything else, Miller claimed the Casa Loma board was giving their own Chair all of the castle's legal work — that he made hundreds of thousands of dollars while the castle deteriorated.) So Miller bought out the Club. And now, 80 years after the city first seized it, the castle on the hill is back in Toronto's hands.

There are again plenty of ideas for how the castle should be used this time around. Rob Ford, unsurprisingly, argued that the city would have to sell it off to private interests. Some want it turned into condos. Or a hotel. There's even a Facebook group asking Drake to buy it and turn it into Casa YOLO.

But with Council's backing, two City Councillors hope they've found a new public use for it. Josh Matlow and Joe Mihevc are asking that part of Casa Loma be turned into a Toronto Museum. Instead of being a monument to the history of one man, it would be a monument to the entire history of our city. Once home to Pellatt's private collection, the castle would now be home to some of the more than 100,000 historic artifacts in the city's collection. The vast majority of them have been sitting in storage, out of public view, waiting for a chance to tell Toronto's story.

That's all assuming, of course, that everything goes well. It won't be easy. Or cheap. The city has been actively trying to find a home for a Toronto Museum for nearly a decade now — first at the Canada Malting silos on the waterfont and then at Old City Hall — without any luck. And no one even knows who the Mayor's going to be a few weeks from now. But they've already started public consultations. And later this month, a Request for Proposal will be sent out, asking for the castle to be used as "an historic attraction and special event venue" with the Toronto Museum as part of the plans.

So maybe, just maybe, after nearly a century spent looking out over the city from that hill above Davenport, after all of those ups and downs — the swanky parties, the tragic neglect, the scandals and the financial collapse — Sir Henry's castle will finally have its happy ending. And if we're lucky, if it all comes together and it's all run by the right people, maybe it will be a happy ending not just for one man, or one family, or one company, but for the entire city of Toronto.

-----

|

|

A version of this story will appear in The Toronto Book of the Dead Coming September 2017 Pre-order from Amazon, Indigo, or your favourite bookseller |

You can listen to The Casa Loma Orchestra play "The Casa Loma Stomp" here.

I wrote a whole big post about that Senator's son, J. Cooper Mason, who survived the armed bank robbery and the Great Boer War before maybe having killed himself over the collapse of the Home Bank. You can check that out here.

I can't resist mentioning how much Sir Henry reminds me of another rotund Conservative millionaire who inherited his business from his father, likes sports, throws huge public parties, has trouble following the rules, fights passionately for the charities he works with while having trouble grasping the idea of the greater public good, and once showed in court to present a case that pretty much boiled down to him being a total fool. Pellatt, like Ford, even once tried to expand his property a bit, by taking over a sliver of adjoining parkland.

I also find Sir Henry's story an interesting compliment to Downton Abbey. He was trying to establish himself as the Canadian equivalent of that fictional family, at the same time that they were realizing that thir old world needed to change.

Bonus quote from a Sir Adam Beck speech in Kingston on Sept. 11, 1910, after the founding of Ontario Hydro: "Our work is only begun. We must deliver power at such a price that the poorest man may have electric light. There will be no more coal oil, no more gas, and I hope in the future, no more coal."

I learned a lot of this information from two books in particular, Sir Henry Pellatt: the king of Casa Loma (buy here, borrow here, read excerpts here) and Casa Loma: Canada's Fairy-Tale Castle and Its Owner, Sir Henry Pellatt (buy here, borrow here). They're both filled with excellent information and many more details and anecdotes about Sir Henry's crooked dealings. There's also a bit more info online here and here and here. And you can learn more about the more recent developments with the Kiwanis Club here, here and here. And about the castle's post-Pellatt years from Torontoist's Jamie Bradburn here. I might end up doing a whole post someday on the SONAR system assembled in Casa Loma's stables. For know, you can learn a little bit more here.

There's some early history of the Home Bank of Canada here. And since individual banks used to print their own money, you can check out what some of their bills looked like here. The Law Society of Upper Canada website has a little bit more about the slum of The Ward here. And the photo I used of the slum was taken by Arthur Goss — blogTO has a whole post of his stuff here. If you're a total nerd, you can read the 1907 Royal Commission on the Life Insurance industry, which called out some of Pellatt's sketchy practices, here.

Finally, one of those old stories Sir Henry liked to tell was about a prank pulled on him by the dude who married his niece: Stephen Leacock — a super-world-famous Torontonian humourist writer guy who was a big influence on comedians like Groucho Marx and Jack Benny. He once sent Pellatt a telegram asking him to pick up the distinguished Sir Thomas at the train station. Sir Henry sent a car, and when the train arrived and the crowd cleared, it turned out that Sir Thomas was a tom cat.

|

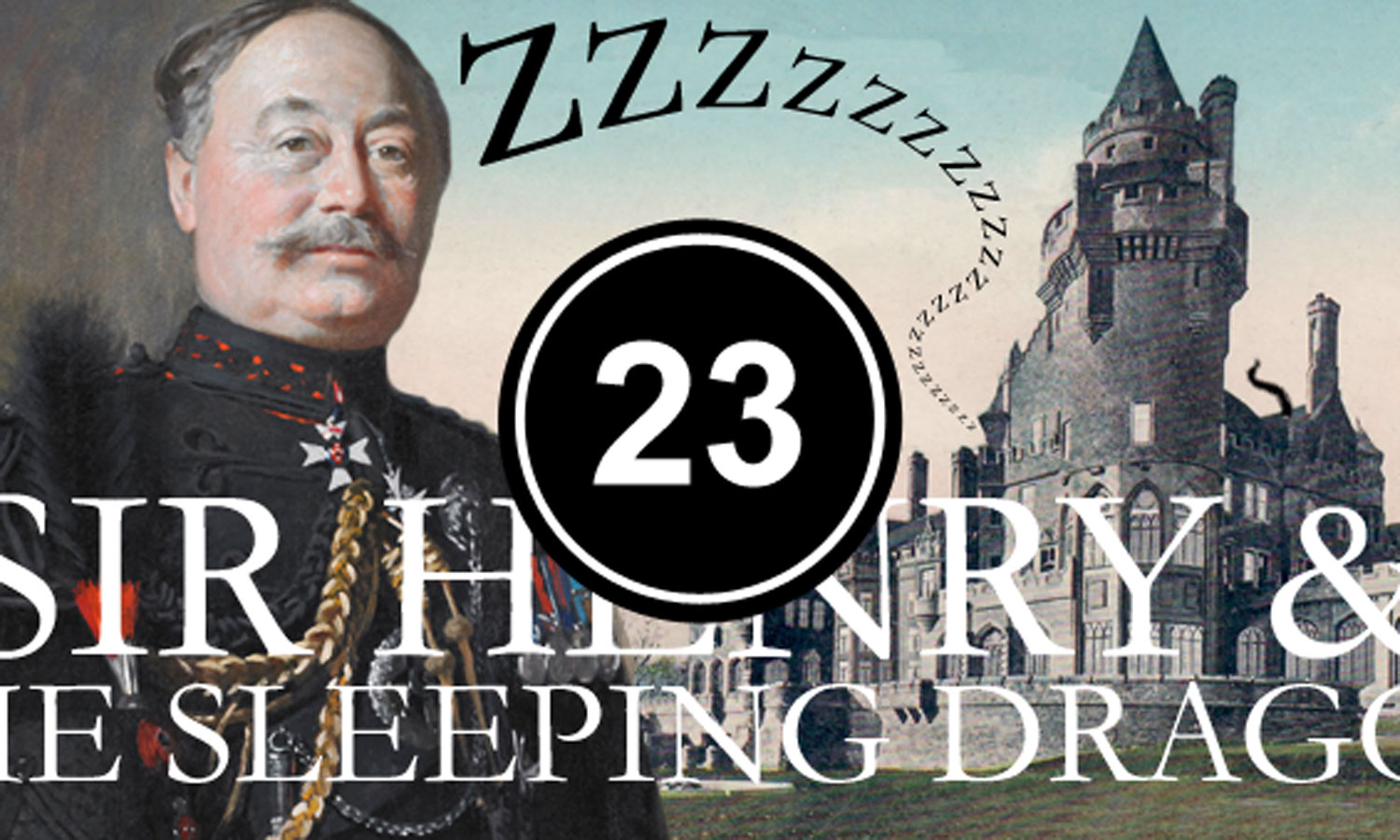

| This post is related to dream 23 Sir Henry & The Sleeping Dragon Sir Henry Pellatt, 1923 |

Thanks, I had been looking for some REAL information about Pellatt. Every other source regales him.

ReplyDeleteI better find a wife soon, get married and have my wedding all around Casa loma, ( house on the hill in Spanish) before they turn it into a zoo. RIP. Sir Henry Pellatt.

ReplyDeleteI'm curious as to the source for your statement that Pellatt and his co-investors in the Electrical Development Company were bought out for more than $30 million. Other sources I've checked say there was no compensation paid for this expropriation. Which is it?

ReplyDeleteSorry, I wrote this long enough ago that I'm not sure what the source for that bit was — or if I made a mistake. I've updated the wording to reflect that.

DeleteThank-you Adam for sharing this, very interesting and informative. Would make for a great period drama movie by Merchant Ivory. I remember climbing the garden walls when I was about ten or eleven and playing in the abandoned, overgrown garden. My Nanny lived down the street and when my mother would leave me there to visit for a week or two, I would get bored and venture to the castle - good times.

ReplyDeleteAdam the way you write with the angst, and the silly comments you made are indication that you are socialist leftist who probably never achieved much in your life and despise the people who did. You probably still rent an apartment and possibly even share it with you mom. Try do do something with yourself. Invest improve things, build something! To see what it takes and if you can handle it. Then you can criticize and say something meaningful. And stop spreading insults and stupidity.

ReplyDeleteglm.... well said, was the exact feel I had while reading, another socialist, upset they don't have a pot to piss in and expect everyone else to pay....

ReplyDeleteThe smartest thing the City of Toronto has done in a century is sign a long term lease with the Liberty Group. Casa Loma looks brilliant today after the disillusioned "public" sector nearly destroyed a magnificent landmark destination.

ReplyDelete