Update: Kevin Plummer, who wrote said excellent Torontoist post, tipped me off to a couple of his other baseball-related Historicist columns. He talks about the T-dot's days as a minor league powerhouse here. And about our players' old-timey baseball cards here. I'm sure to steal liberally from both at some point down the line...

Thursday, March 31, 2011

Photo: Playing Baseball At Riverdale Park in 1914

Update: Kevin Plummer, who wrote said excellent Torontoist post, tipped me off to a couple of his other baseball-related Historicist columns. He talks about the T-dot's days as a minor league powerhouse here. And about our players' old-timey baseball cards here. I'm sure to steal liberally from both at some point down the line...

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

The Yonge Street Riot of 1992

|

| Queen Street during the G20 |

But our riots aren't a thing of the distant past. In the late-1980s and early '90s, we'd riot every time the Ex closed for the year. We rioted on New Year's Eve to ring in 1992. And then, a few months later, when white cops beat a black man in Los Angeles and were acquitted, we rioted again. As South Central L.A. exploded into flames and destruction, a small group in Toronto protested the Rodney King case outside the U.S. consulate on University. Soon, the crowd had swelled and some turned violent. Something like a thousand people marched up Yonge Street, smashing windows, overturning hot dog carts and generally being destructive assholes. From the footage, it looks like some were even throwing molotov cocktails.

Somehow, that time, the police managed to handle the situation without completely ignoring due process or arresting more people than ever before in the entire history of the country. There were about 30 arrests, a few injuries, and—despite the usual warnings that "we might just see the face of downtown Toronto changing forever"—things got back to normally pretty quickly. So much so that twenty years later most people seem to have forgotten it ever happened.

Here's the Citytv coverage from the day after, complete with painfully punny titles and an adorably young Ben Chin:

Thursday, March 24, 2011

Elizabeth Taylor's Love Nest

Cleopatra was a BIG movie. It had lavish sets. Elaborate costumes. Thousands of extras. It was the most expensive film ever made. It ran more than four hours long. It won four Oscars, earned more money at the box office than any other movie in 1963 and still managed to lose tens of millions of dollars. But nothing about it was as big as its stars. Elizabeth Taylor, hailed as one of world's most beautiful women (um, see left), became the highest paid actress in Hollywood when she signed on to play the title role. And starring alongside her as Marc Antony was one of the most respected thespians of his time: Richard Burton.

But this was back in the days when divorces were super-hard to get, so they'd had to go to Mexico for it. And Taylor's was taking even longer. That was a problem. Burton, you see, was returning to the stage in a John Gielgud-directed production of Hamlet. It was debuting in Toronto at the O'Keefe Centre. Which meant that since the two lovers didn't want to be away from each other, they would be living here. Together. For eight weeks. In sin.

They arrived in January of 1964 and took over a five-room suite on the eighth floor of the King Edward Hotel. (Good luck finding a newspaper article that doesn't refer to it as a love nest.) And oh man, did some people freak out. There was no shortage of religious nutjobs back in the early 1960s. The Vatican had already denounced Taylor's "erotic vagrancy". Judgmental teenagers showed up at the hotel with signs saying creepy things like "Drink not the wine of adultery" and "She walks among your children". A congressman in the States even suggested that Burton's U.S. visa should be revoked.

|

| Taylor & Burton at the King Edward Hotel |

Nine days after Taylor's own Mexican divorce was finalized, the couple were married—in Montreal, since Ontario wouldn't recognize their quickie, foreign divorces. A couple of days later, they were back in Toronto showing off their wedding rings. The minister who performed the ceremony would be getting angry phone calls for weeks.

A few days after they got back, Taylor and Burton were off to the States; Hamlet opened on Broadway. Over the course of the '60s, they'd make seven movies together and drink and fight and write passionate love letters declaring their undying love. He called her "a poem", "unquestionably gorgeous", "extraordinarily beautiful" and also "famine, fire, destruction and plague". They divorced in 1974. Remarried in 1975. Then divorced again in 1976. That would be for the last time; a few years later he was dead.

When she came home from the memorial service, there was one last love letter waiting for her in the mail. He'd written it three days before he died, asking her to give him one more chance. In one of the last interviews she gave before she died in 2011, she said it was still there, where she kept it, in the drawer beside her bed.

I cobbled most of this story together from articles in the Toronto Star and on the CBC, which you can read here and here and here. And there's more about them (with more passionate quotes) here and here and here.

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

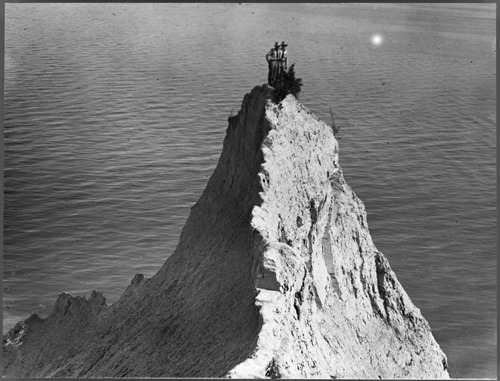

Photo: Scaling The Bluffs in 1909

Sunday, March 20, 2011

From The Graveyard Of The British Empire

|

| The durbar for King Edward VII, 1903 |

We'll get to Toronto by the end of this story, I promise, but we start in India, at a place called Coronation Park. It's a grand, wide-open space on the edge of Delhi, the dusty capital of what will soon be the most populous nation in the history of the world, a city teeming with more than 12 million people. It was right here, in this park, that the British threw their biggest parties to celebrate their rule over the "crown jewel" of their empire. The first one was in 1876, to honour the day Queen Victoria was crowned as the Empress of India. There was an immense, lavish procession, with the country's most important British officials riding in on elephants and 70,000 people in the crowd.

When Queen Victoria died and the crown was passed down to her son, King Edward VII, they did it all over again. This time, the durbar (which is what they called these things) was even bigger. The celebrations went on for two weeks. More than 100,000 people showed up. There were fireworks. Parades. Even polo matches. An entire city of tents rose up on the grounds, supplied with their own electricity, running water and rail lines. There were commemorative stamps printed. Maharajas, Viceroys and Governors came from all over India. The King's own brother even made the trip from England.And that was nothing. A few years later, King Edward was dead. And the new one, King George V (who you probably know as Colin Firth's dad in that movie), decided he wanted to attend his durbar in person. He and his Queen sat on golden thrones under golden umbrellas as 80,000 Indian troops paraded through the park before them. There were vast seas of horses and camels and cannons. King George even seized the moment to declare that Delhi would be the new capital of India.

Of course, the whole thing was a giant pile of horseshit; a pretty facade to help mask the vile things they were doing. At the Jallianwala Bagh massacre they ordered fifty British Indian Army troops to fire on a trapped crowd of unarmed men, women and children for ten to fifteen minutes until their ammunition ran out. By the end there were more than a thousand bodies on the ground. At the Qissa Khawani Bazaar massacre, they drove armoured cars through crowds of non-violent demonstrators, used machine guns on the ones who refused to leave the injured behind and then hunted the rest through the streets for hours. The members of a regiment who refused to fire on the crowd were all arrested. Some got life in prison.

But the Indian demonstrators, led by heroic figures like Mahatma Ghandi, would eventually win. India declared independence soon after the Second World War. And Coronation Park became nothing more than a reminder of a terrible time. So it was left to decay; the grounds mostly untended, overgrown with trees and shrubs. And it wasn't the only symbol of colonial rule left in Delhi. All over the city, the British had erected monuments to their kings and queens and aristocrats. And all over the city, people didn't want them anymore. So they were pulled down off their pedestals, rounded up, and shipped to Coronation Park, where they were tucked away in an obscure corner and forgotten.

|

| Coronation Park |

We're interested in one statue in particular. It's of Kind Edward VII, who ruled in the early years of the 1900s. His statue was designed by a big deal royal sculptor guy, the same one who built the giant memorial to Queen Victoria that towers outside Buckingham Palace. His bronze Edward sat astride his horse in Delhi's Edward Park, just across the street from the medieval Red Fort which had served as the Mughal capital in India for centuries before the British drove them out. And the statue even got a bonus plaque when King George swung by during his durbar to pay tribute to the tribute to his father. But after the fall of the empire, the Indian government renamed Edward Park after one of the heroes of the independence movement, put up a statue of him instead, and had King Eddie join the other relics.

|

| King Edward VII in Queen's Park |

Thursday, March 10, 2011

Photo: A Monster Atop Old City Hall, 1920

Sunday, March 6, 2011

Tragedy At Hogg's Hollow

|

| Rescue efforts |

Toronto has been, in the most literal way possible, built by immigrants. English hands raised the timbers of Fort York. Germans carved Yonge Street out of the forest. Irishmen and Italians, Ukrainians, Poles and people from all over the world have built our bridges, paved our streets and erected one of the tallest buildings in the history of the world.

The city's Italian community was devastated. In the wake of the disaster, a fund was set up to help the victims' families and Johnny Lombardi (the friendly old fellow who ran CHIN until he died a few years ago) held a benefit concert at Massey Hall. On the political front, the Toronto Telegram led the charge, running one front page story after the other with headlines like "SLAVE IMMIGRANTS" until, finally, the provincial government ordered a Royal Commission to investigate. In the end, stricter safety and labour laws were passed.

And that's pretty much been it. As the Toronto Star pointed out in an article last year, the laws haven't really been updated since. More than 400 construction workers in Ontario have died on the job since 1990—most of them in gruesome and preventable ways: crushed by equipment, fallen from scaffolding, drowned, electrocuted, sliced open. And as employers continue find ways around the fifty-year old laws, those numbers are expected to go up.

|

|

A version of this story will appear in The Toronto Book of the Dead Coming September 2017 Pre-order from Amazon, Indigo, or your favourite bookseller |

|

| This post is related to dream 03 The Death of Giovanni Fusillo Giovanni Fusillo, 1960 |