On the first night of The Toronto Dreams Project's UK Tour, I headed straight for the most famous place in London: Westminster. In my pocket, I was carrying a dream for one of the most interesting scientists from the history of Toronto: Sir John Henry Lefroy. I made my way through the hordes of tourists and — in a moment when it seemed like no one was watching — I left the dream here, in the middle of Westminster Bridge. I left it here because this is the spot where Lefroy was standing in the early afternoon of June the 28th, 1838 — at the exact moment when the Imperial State Crown was first placed upon Queen Victoria's head.

Lefroy was still just a teenager back then, a young lieutenant in the Royal Artillery. But it was only a few years later that he began the scientific work that would make him famous. When the British government decided to study the Earth's magnetic field — to figure out why it kept changing — Lefroy was chosen to play an important role in the project. So, by the time he was 25, he found himself living in Canada as the superintendent of "Her Majesty's Magnetical and Meteorological Observatory at Toronto".The original facility was built on the grounds of what's now the University of Toronto, right next to where Convocation Hall is today. There's a plaque for Lefroy there. And there's a slighter newer version of the observatory that still stands on the lawn outside Hart House. Plus, there's an even more recent version: the building where the Monk Centre is now (on Bloor Street just west of Varsity Stadium).

While he was in Canada, Lefroy also made a famous trek into the Northwest Territories, travelling more than 8,000 kilometers with a team from the Hudson's Bay Company. He took hundreds of measurements along the way, getting even further north and further west than Yellowknife. Thanks to that trip, there's now a mountain in the Rockies named after him. And he became the subject of a Paul Kane painting. It's called Scene in the Northwest: Portrait of John Henry Lefroy, or, sometimes, The Surveyor. They've got it at the AGO. It's the most expensive painting in Canadian history. The Toronto billionaire Ken Thomson (who owned the Globe & Mail, the London Times and all sorts of other stuff) paid more than $5 million for it in 2002. That's more than double the previous record.

|

| Paul Kane's The Surveyor |

He also married a Torontonian. Emily Mary Robinson was the daughter of Sir John Beverley Robinson: a hero of the War of 1812, a Tory judge, and a hardcore member of the Family Compact who infamously sentenced two of William Lyon Mackenzie's rebels to death. Funny enough, she was also cousins with the Boultons: the family who built the Grange, the house that would eventually become the AGO, where that $5 million portrait now hangs.

Eventually, Lefroy headed back home to London and continued to lead a fascinating life. He teamed up with Florence Nightingale to reform the army, spent years as the Governor of Bermuda, and travelled all the way to the other side of the world to be the Administrator of Tasmania. He spent the rest of his life as of the senior figures of the British Empire — all in the heyday of Queen Victoria's reign.

Which brings me all the way back to that day in 1838, when Lefroy was a teenaged lieutenant standing on Westminster Bridge.

The coronation of the young queen — only a teenager herself back then — was, of course, a Very Big Deal. London was buzzing. There were special songs written, special medals given, special ribbons designed. Huge crowds gathered. There were military bands and long lines of horses and soldiers. Guns fired a salute at dawn and then again when Victoria left Buckingham Palace in her carriage, part of a lavish procession of royalty and soldiers and ambassadors and officials. Decades later, the Sydney Morning Herald remembered the moment: "As the procession passed on through the streets—where sidewalks, balconies, windows, and the very roofs (where possible) seemed alive with spectators waving scarves and handkerchiefs, and shouting their loyal greetings—the sight was one never to be forgotten by those who witnessed it."

Finally, Victoria arrived at Westminster Abbey, where the coronation would take place. It's a absolutely stunning church even on an ordinary day. I visited the Abbey on my last morning in London; it's spectacular, home to breathtaking history, including the bones of monarchs like Elizabeth I and Henry V, scientists like Darwin and Newton, and writers like Dickens, Chaucer, Tennyson and Kipling. On this day, it was even more beautiful than usual. The floors and walls were draped in cloth of crimson, purple and gold. The most hallowed royal relics were on hand, ready to play their part in the ceremony. And the most important people in the Empire had gathered to watch it all happen.

|

| The Coronation of Queen Victoria |

But at the last minute a big, famous military official learned about the plan and chose someone else instead. So, rather than getting to give the signal, Lefroy was now supposed to receive the signal and pass it along to the soldiers at the Tower of London, just around the bend of the Thames, so they could let the crowd there know that their queen had been crowned.

So, when the big moment happened, John Henry Lefroy wasn't perched high above his monarch, in the middle of all the action. Instead, he was outside, as he later remembered: "posted in the centre of... Westminster Bridge, in full uniform, to enjoy the jeers of the populace that came pouring in from Lambeth and the Old Kent Road."

|

| Westminster Abbey |

|

| St. Martin in the Fields on Trafalgar Square where Lefroy was baptised by the Bishop of London |

|

| 1 Savile Row, formerly the Royal Geographical Society The Bealtes played their rooftop gig next door |

|

| A dream for Lefroy at the old Geographical Society where he was a member |

|

| Swanky Cambridge Terrace, where Lefroy lived overlooking Regent's Park |

|

| Burlington House, home to the Royal Society |

|

| A dream for Lefroy outside the Royal Society where he was a member |

|

| The Royal Automoblie Club on Pall Mall formerly the Ordnance Office |

|

| A dream outside the Ordnance Office which Lefroy used to run |

|

| St. George's Hanover Square |

|

| A dream at St. George's Hanover Square where Lefroy married his second wife |

|

| The view toward Westminster Bridge |

John Henry Lefory's autobiography, where that last quote comes from, is available to read for free at Archive.org here. The details and description of the coronation came from the Sydney Morning Herald via Queen Victoria Online, which you'll find here. And there's more information about the history of Toronto's magnetic observatory on Wikipedia here.

Both paintings come via the Wikimedia Commons.

|

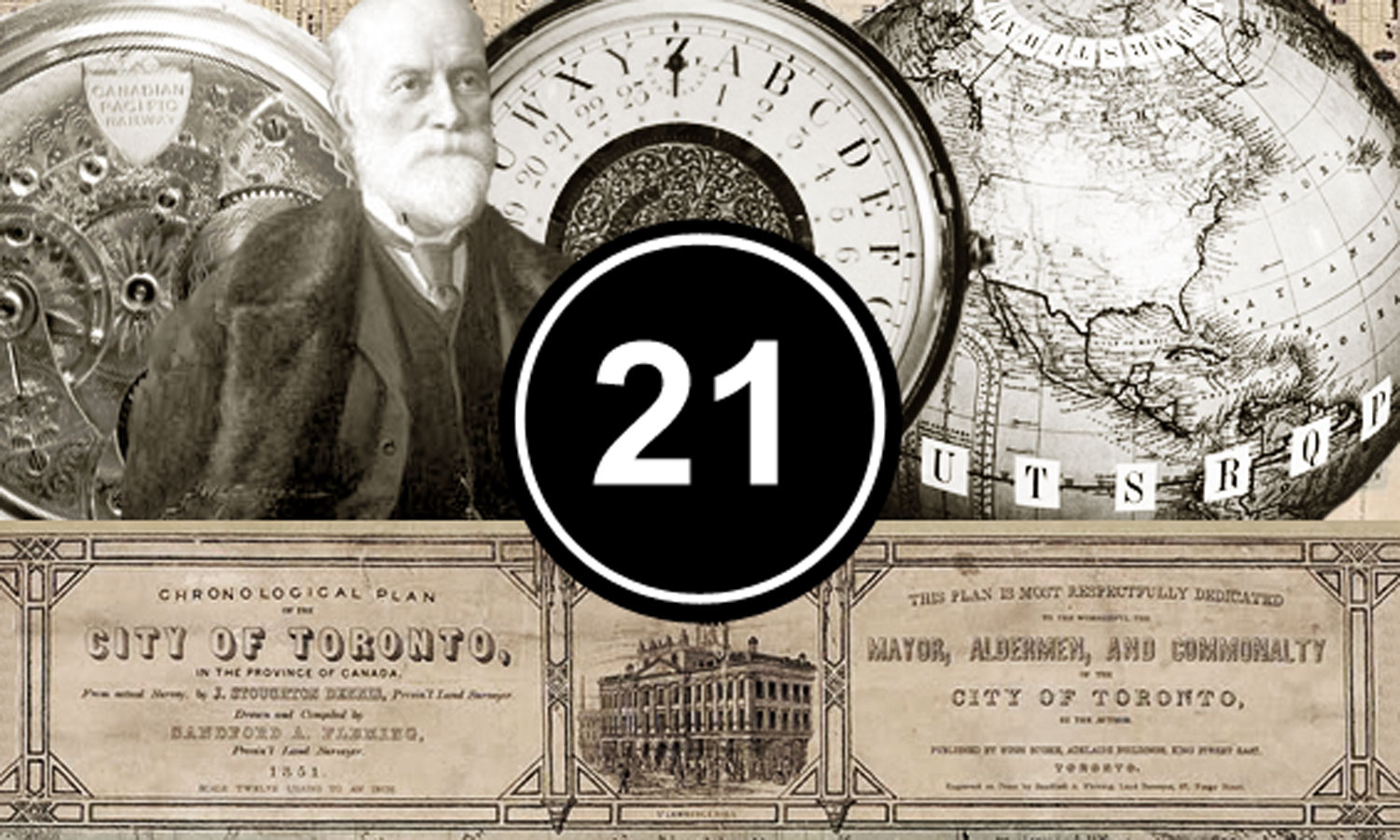

| This post is related to dream 33 The Magnetic History of Toronto John Henry Lefroy, 1847 |

|

| This post is related to dream 31 Saving the Canadian Artist Paul Kane, 1865 |