This photo is looking north up Yonge Street from Queen Street in 1915ish. I don't have too terribly much to say about it, but here are a few tidbits. The entire left-hand side of the photo, the west side of Yonge, is now, of course, the Eaton's Centre. But the H. Knox and Company store you see here (which eventually become Woolworths) is still partially preserved. Across, the street from it, on the very right of the photo is the Bank of Montreal building which is also still there on the north-east corner of the intersection, though now it has a giant glass tower rising out of it. Behind that, you can see part of the sign for the Heintzman piano company, which will get its own post someday. Theodore August Heintzman came to Toronto from Germany in the 1800s and built a piano in his kitchen. When he sold it, he used the money to start his own company, which soon gained an international reputation for producing some of the highest quality pianos in the world. In 1915, Heintzman had recently bought the building you see here to use as a head office; we still call it "Heintzman Hall". These days, it's a heritage property and home to a Home Sense.

Tuesday, January 31, 2012

Thursday, January 26, 2012

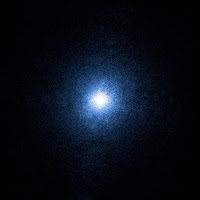

The Very First Black Hole Ever Discovered Was Discovered At U of T

|

| HDE226868 |

This is a photo of a star called HDE226868. It's a blue supergiant, more than 20 times as big – and hundreds of thousands of times as bright – as the Sun. And it's relatively close by, in the same part of the galaxy as we are: a thin line of stars in between two of the great spiraling arms of the Milky Way. Still, it takes light 1600 years to reach us from there. It's about 16 quadrillion kilometers away. And you can't see it with your naked eye; you need at least a small telescope to glimpse it through the clouds of interstellar gas and dust that stand between us and it.

But as far as X-rays go, this patch of sky is a shinning beacon. The signal we get from it is stronger than pretty much anything else we can see. And since blue supergiants don't give off that kind of radiation, we know those X-rays must be coming from something else. Something powerful. Something we call Cygnus X-1.

Charles Thomas Bolton figured that Cygnus X-1 was probably another star. He was just a young astronomer back in 1971, having come up from the States to do his postdoc at the University of Toronto. He spent a lot of his time at the school's astronomy facility in Richmond Hill: the David Dunlap Observatory. The beautiful stone and dome complex had been built in the 1930s on an estate of nearly two hundred acres just north of the city. It housed the second biggest telescope in the world when it opened. William Lyon Mackenzie King was here to help celebrate the opening. Stuttering King George and his wife Elizabeth (who you might know better as the Queen Mum or Helena Bonham-Carter in The King's Speech) made sure to see it on their trip across Canada. It's still the biggest telescope in the country. And when Bolton pointed it at Cygnus X-1, he was hoping to find evidence of a neutron star.

Neutron stars are small but incredibly heavy, the dense remnant of a bigger star after it dies in a supernova explosion. They give off X-rays like crazy. And early observations seemed to confirm Bolton's suspicions: he could see that HBE226868 was wobbling slightly, which meant that there must be a massive source of gravity nearby. If that source of gravity was a neutron star, he'd have discovered a binary system: two stars orbiting around each other. That would have been a pretty exciting find for the young astronomer, who was particularly interested in those systems.

Neutron stars are small but incredibly heavy, the dense remnant of a bigger star after it dies in a supernova explosion. They give off X-rays like crazy. And early observations seemed to confirm Bolton's suspicions: he could see that HBE226868 was wobbling slightly, which meant that there must be a massive source of gravity nearby. If that source of gravity was a neutron star, he'd have discovered a binary system: two stars orbiting around each other. That would have been a pretty exciting find for the young astronomer, who was particularly interested in those systems.

But Cygnus X-1 was no neutron star. After a couple of months spent collecting data at the Dunlap Observatory, Bolton began to suspect the truth about what he'd actually found. HDE226868 was orbiting something massive, alright. But it was orbiting it at an incredible speed: more than 200 times the speed of sound. That meant Cygnus X-1 was much smaller and much denser than a neutron star. It meant Cygnus X-1 was a black hole.

It seems that once upon a time, there was a really, really, really, really, really BIG star. Like more than 40 times bigger than the Sun big. For most of its life, it did what all stars do: crush hydrogen atoms together, the immensity of its gravity causing nuclear reactions to fuse them into helium. In fact, it was so big that eventually it was fusing that helium into even more complex elements, stuff like carbon and neon and oxygen and silicon. That's where all that stuff comes from: every single atom of it in the entire universe forged within a star. By the end of their lives, the very biggest stars make an even more complex and heavier element: iron. And so, at the centre of this particular gigantic star, a great iron core was building up. In the end, it was so heavy that its atoms couldn't support its own weight anymore. It imploded. The enormous mass was crushed down into a tiny space. It became so dense, and its gravity so strong, that nothing that came close to it could ever escape again. Not even light. It became a black hole.

|

| An artist's conception of Cygnus X-1 and HBE226868 |

Now, no one had ever found a black hole before. Einstein's theories of relatively – and the quantum physics that followed – had predicted them, but there were still plenty of scientists who didn't believe they existed at all. Bolton knew that going public with his discovery was going to be risky. It would either make or break his career. It wasn't until a pair of scientists in England – and then another one in the United States – seemed to confirm his findings that he published his paper. Even then, it was extremely controversial. People put forward plenty of arguments against it. It even became the subject of a famous bet between Stephen Hawking and another physicist, Kip Thorne. Hawking, who had long believed in black holes, says he was 80% sure that Bolton was right, but bet against it anyway. That way, even if he'd been wrong about black holes his entire career, he'd still win something.

But he wasn't wrong. In 1990, enough evidence had finally piled up to convince Hawking without a doubt. Bolton had been right. Cygnus X-1 was a black hole. The David Dunlap Observatory had discovered an extraordinary phenomenon never seen before. Hawking broke into Thorne's office at night and signed the bet. Thorne had officially won himself a one-year subscription to Penthouse magazine.

-----

These days, black holes are widely-accepted as an important part of our universe. And supermassive black holes, waaaay bigger than Cygnus X-1, are believed to sit at the centre of many galaxies — including the Milky Way.

Tom Bolton still works as a professor at U of T, though they recently kicked him out of the David Dunlap Observatory so they could sell it to a developer, who has promised to preserve the facility itself. It's still open to the public, which more details on their webiste here.

As for the open land around it? That's currently being fought over at the Ontario Municipal Development Board. The developer wants to build on it, while community groups want to preserve the parkland, protect local wildlife (like this baby coyote, awwwww), and ensure that light pollution doesn't interfere with the view through the telescope. You can read about the fight here and support those who want to protect the land here.

In the late-'70s, Toronto prog-rockers Rush wrote a 28 minute-long, two part song about Cygnus X-1, which spanned two albums and tells the story of a spaceship captain who is pulled into the black hole only to find himself in the Greek mythological home of the gods, Olympus, where he settles a conflict between Apollo and Dionysus, and then becomes a god himself. You can listen to the whole crazy thing right here.

Also interesting: the Dunlap's telescope mirror was carved from the same glass the famed Palomar telescope in California, which inspired an Italo Calvino book and a Rheostatics song.

You can read a bit more about Tom Bolton in the U of T paper here.

And here's a sketch of the plans for the observatory, drawn in 1933, along with a couple of my favourite more recent photos of it:

Tom Bolton still works as a professor at U of T, though they recently kicked him out of the David Dunlap Observatory so they could sell it to a developer, who has promised to preserve the facility itself. It's still open to the public, which more details on their webiste here.

As for the open land around it? That's currently being fought over at the Ontario Municipal Development Board. The developer wants to build on it, while community groups want to preserve the parkland, protect local wildlife (like this baby coyote, awwwww), and ensure that light pollution doesn't interfere with the view through the telescope. You can read about the fight here and support those who want to protect the land here.

In the late-'70s, Toronto prog-rockers Rush wrote a 28 minute-long, two part song about Cygnus X-1, which spanned two albums and tells the story of a spaceship captain who is pulled into the black hole only to find himself in the Greek mythological home of the gods, Olympus, where he settles a conflict between Apollo and Dionysus, and then becomes a god himself. You can listen to the whole crazy thing right here.

Also interesting: the Dunlap's telescope mirror was carved from the same glass the famed Palomar telescope in California, which inspired an Italo Calvino book and a Rheostatics song.

You can read a bit more about Tom Bolton in the U of T paper here.

And here's a sketch of the plans for the observatory, drawn in 1933, along with a couple of my favourite more recent photos of it:

Thursday, January 19, 2012

People Were Pissy About Toll Roads Back in the 1800s, Too

|

| Toll house, Dundas & Bloor |

So that's what a toll house in Toronto looked liked in the 1800s. This one was apparently on the northeast corner of Bloor and Dundas. But the very first one we ever built in the city was on Yonge Street, at King, back in 1820. That's when there were still only about a thousand people living here, in a tiny little town nestled between the lake and the ancient, wild forest that had stood on this land for thousands of years. It hadn't even been three decades since the first British soldiers showed up to chop down trees and clear space for Upper Canada's new capital. So, in those days, even Yonge Street and King Street were just rough, muddy paths. And their intersection, now at the bottom of a canyon of skyscrapers, wasn't much more than a crossroads in the countryside, a few blocks west of the heart of the town. Building those early, rudimentary roads and keeping them passable was a pretty big job; collecting tolls helped pay for it. Soon, there were toll houses all over Toronto.

That, of course, pissed some people off. And some of them tried to avoid paying tolls altogether. That was a common practice back then — and not just in Toronto. Cornelius Krieghoff, one of the most famous and iconic early Canadian artists, has a whole series of paintings about people whipping their horses up to full speed so they could blow past toll houses without paying. Back in Wales, people rioted, men dressing up as women to destroy toll-gates under the cover of darkness. They called themselves Rebeccaites after Genesis 24:60: "And they blessed Rebekah and said unto her... let thy seed posses the gate of those which hate them."

In Toronto, things could get tense too. Along Queen Street, there was an important toll house built at what's now Ossington but was then the end of Dundas, the major road stretching west all the way to London. To the south of the toll-gate was an enormous military reserve – and Fort York. So if you wanted to sell stuff to the British army, you had to pay a toll every time. This especially annoyed one particular lumber dealer. His men frequently got into fights with the toll collectors – sometimes there was violence. Finally, the lumber dealer bought the plot of land to the east of the toll house and built his own damn path through the woods. That way, his men bypassed the toll-gate altogether. He called his new road Rebecca Street, in honour of those Welsh rebels. And it's still there today, branching off Ossington a block north of Queen.

There were toll houses in Toronto for nearly a hundred years. But by the end of the 1800s, the last of them were closed as part of an agreement to let people from outside the city sell their goods at the St. Lawrence Market free of any fees. (You can still visit one, though: the "tollkeepers cottage" was recently restored on the north-west corner of Davenport and Bathurst.)

Fifty years after that, some people, including our mayor, would propose building the Gardiner Expressway as a toll road, but that part of the plan never happened. So it wasn't until the 1990s that Bob Rae's provincial government would build the 407 to raise funds for the government (and then Mike Harris' government would essentially just sell it off to a private consortium to help balance his budget just before an election). It was the first toll road in the world without gates, operating electronically instead. And it was the first toll road in Toronto in more than century.

Fifty years after that, some people, including our mayor, would propose building the Gardiner Expressway as a toll road, but that part of the plan never happened. So it wasn't until the 1990s that Bob Rae's provincial government would build the 407 to raise funds for the government (and then Mike Harris' government would essentially just sell it off to a private consortium to help balance his budget just before an election). It was the first toll road in the world without gates, operating electronically instead. And it was the first toll road in Toronto in more than century.

-----

You can read more about the Tollkeepers Cottage here. I found the painting of the toll house on the Toronto Public Library website here. You can read a bit about Rebecca Street and the connection to the Rebeccaites here. And more about those Welsh rebellions here and here. I was first tipped off to the story by the book Toronto Street Names: An Illustrated Guide to their Origins, which my parents got me for Christmas and rules. You can buy it yourself here or get at the library here.

Sunday, January 15, 2012

Botany Classes Used To Really Overdress

Thanks to the fact that people back in the Edwardian era were crazy and stylish and deathly afraid of accidentally showing any skin, this is apparently what a botany class from the University of Toronto looked like back in 1910. Even when they were on a field trip tramping through the swamps of High Park.

Thursday, January 12, 2012

The Next Little Red Umbrella Variety Spectacular

As some of the more regular readers of the blog may already know, when I'm not writing stuff over here, I'm usually writing stuff over at The Little Red Umbrella. We've recently started doing live events, mishmashes of readings and lectures and comedy and music, with a some history of Toronto stuff included, too. So I thought I'd take the opportunity to let you know about the next one, which is coming up on Friday, January 20th at the Holy Oak Cafe.

Jason Kucherawy, of Tour Guys, will be telling some Toronto history stories, author Shaughnessy Bishop-Stall will be reading from his novel, Ghosted, magician James Alan will be defying the laws of physics and reason right before your very eyes, Blood Rexdale and the Walls are Blonde will be playing shoegazey rock, and comedian Desiree Lavoy-Dorsch will be telling her hilarious jokes. Then, at the end of the night, DJ Flex Rock will play songs you can dance around to.

I'm hosting, the whole thing is free and 10% of bar sales go to support the AIDS Committee of Toronto. The drinking starts at 9, the show starts around 9:30. And the Holy Oak is at 1241 Bloor Street West (just east of Lansdowne).

You'll find the Facebook invite here.

Tuesday, January 10, 2012

The Red Lion Inn, One Of Our First and Most Important Buildings

|

| The Red Lion Inn |

Okay, so I'm pretty excited about having stumbled across this photo. That's the Red Lion Inn – one of the very first buildings anyone ever built in Toronto. You come across it pretty often while you're reading about the early history of our city, but it's so old — and was torn down so long ago — that it never occurred to me there might actually be a photo of it out there somewhere.

It was on east side of Yonge Street, just north of Bloor. When it was built in 1808, our little town of York was still only 15 years old, far away to the south, just a few muddy blocks along the shore of the lake. The inn was built by one of Toronto's earliest settlers, Daniel Tiers, who seems to have come here as part of a group of mostly Germany immigrants. You hear a lot about those Germans when you read up on Toronto's early history too. They were promised free land in return for clearing Yonge Street out of the forest, from Eglinton all the way up to Lake Simcoe. They built the road, but never got their land, screwed over by the racist, rich British folk who ran our town back then.

When Tiers first built his inn, it would have been surrounded by an immense wilderness, an oasis in the middle of a forest thousands of years old. There were still wolves and bears in these parts back then, bald eagles and deer and foxes and flocks of passenger pigeons so thick they could block out the sun. But things changed fast. And even though it was well outside town, the intersection of Bloor and Yonge, with Davenport Road nearby, was already an important crossroads on the way down into the tiny new capital, where government business, the St. Lawrence Market, and a port to the rest of the world were waiting. Before long an entire village had sprung up around the Red Lion. They called it Yorkville. The settlement was founded by Joseph Bloor (who owned a brewery nearby and was extremely scary-looking) and our very first sheriff, William Botsford Jarvis (whose country estate, Rosedale, was just across the valley and who would play an important role in defeating William Lyon Mackenzie's famous rebellion).

Soon, the picturesque little village was functioning as an early suburb of Toronto, with people living there, but working downtown. And so, by the mid-1800s, our city had gotten its very first horse-drawn bus line. It was founded by a cabinet maker, who had the carriages made in his cabinet-making shop. Every ten minutes, another coach would leave the Red Lion Inn heading down Yonge Street into the capital. A couple of decades later, they were replaced by Canada's very first streetcar line.

The Inn was also, like most places where you could get drunk, an important meeting place. They say that in the lead up to that famous Rebellion of 1837, William Lyon Mackenzie's supporters would gather at the inn to plan their attack. And when Mackenzie had been undemocratically kicked out of parliament by the democracy-loathing Tory Party, it was at the Red Lion Inn that he was immediately re-elected — an important moment in the struggle to make Canada a true democracy.

Yorkville carried on as a quiet residential village of Victorian homes until the 1880s, when it was finally officially swallowed up by the city of Toronto. Nearly a hundred years later, in the late 1950s, those same homes would be converted into the smoke-filled coffee houses of our Beatnik scene — where poets like Margaret Atwood, Dennis Lee and Gwendolyn Macewen got their starts. Before long, the Beats gave way to the hippies and those coffee houses were turned into rock 'n' roll and folk music clubs, home to the likes of Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Gordon Lightfoot. It wasn't until the late-'60s that the authorities decided to "eradicate" the scene, driving the hippies out to replace them with the high-end boutique shopping district that dominates Yorkville today — one of the most expensive retail strips in the world.

It was on east side of Yonge Street, just north of Bloor. When it was built in 1808, our little town of York was still only 15 years old, far away to the south, just a few muddy blocks along the shore of the lake. The inn was built by one of Toronto's earliest settlers, Daniel Tiers, who seems to have come here as part of a group of mostly Germany immigrants. You hear a lot about those Germans when you read up on Toronto's early history too. They were promised free land in return for clearing Yonge Street out of the forest, from Eglinton all the way up to Lake Simcoe. They built the road, but never got their land, screwed over by the racist, rich British folk who ran our town back then.

When Tiers first built his inn, it would have been surrounded by an immense wilderness, an oasis in the middle of a forest thousands of years old. There were still wolves and bears in these parts back then, bald eagles and deer and foxes and flocks of passenger pigeons so thick they could block out the sun. But things changed fast. And even though it was well outside town, the intersection of Bloor and Yonge, with Davenport Road nearby, was already an important crossroads on the way down into the tiny new capital, where government business, the St. Lawrence Market, and a port to the rest of the world were waiting. Before long an entire village had sprung up around the Red Lion. They called it Yorkville. The settlement was founded by Joseph Bloor (who owned a brewery nearby and was extremely scary-looking) and our very first sheriff, William Botsford Jarvis (whose country estate, Rosedale, was just across the valley and who would play an important role in defeating William Lyon Mackenzie's famous rebellion).

Soon, the picturesque little village was functioning as an early suburb of Toronto, with people living there, but working downtown. And so, by the mid-1800s, our city had gotten its very first horse-drawn bus line. It was founded by a cabinet maker, who had the carriages made in his cabinet-making shop. Every ten minutes, another coach would leave the Red Lion Inn heading down Yonge Street into the capital. A couple of decades later, they were replaced by Canada's very first streetcar line.

The Inn was also, like most places where you could get drunk, an important meeting place. They say that in the lead up to that famous Rebellion of 1837, William Lyon Mackenzie's supporters would gather at the inn to plan their attack. And when Mackenzie had been undemocratically kicked out of parliament by the democracy-loathing Tory Party, it was at the Red Lion Inn that he was immediately re-elected — an important moment in the struggle to make Canada a true democracy.

Yorkville carried on as a quiet residential village of Victorian homes until the 1880s, when it was finally officially swallowed up by the city of Toronto. Nearly a hundred years later, in the late 1950s, those same homes would be converted into the smoke-filled coffee houses of our Beatnik scene — where poets like Margaret Atwood, Dennis Lee and Gwendolyn Macewen got their starts. Before long, the Beats gave way to the hippies and those coffee houses were turned into rock 'n' roll and folk music clubs, home to the likes of Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Gordon Lightfoot. It wasn't until the late-'60s that the authorities decided to "eradicate" the scene, driving the hippies out to replace them with the high-end boutique shopping district that dominates Yorkville today — one of the most expensive retail strips in the world.

-----

I found the photo on Wikipedia here. And there's a page about that first bus line here. You can read little bits and pieces about the Inn and its owner here and here and here and here and here.

|

| This post is related to dream 10 The Battle of Montgomery's Tavern William Lyon Mackenzie, 1837 |

Wednesday, January 4, 2012

Damn, That's One Fine-Looking Post Office

This was our eighth General Post Office. It was on Adelaide, just a couple of blocks east of Yonge, at the head of Toronto Street. And it was, as you can see in this postcard from the very early 1900s, totally awesome.

That's because it was designed by Henry Langley, one of Toronto's most totally awesome architects. He also built a whole hell of a lot of our most beautiful churches: St. Michael's Cathedral at Church and Dundas; Metropolitan United at Church and Queen; Trinity-St. Paul's at Bloor and Spadina; Jarvis Street Baptist and St. Andrew's on the edges of Allan Gardens. He even did the delicate chapel at the Necropolis cemetery in Cabbagetown, where he's buried on the slopes of the Don Valley alongside the likes of William Lyon Mackenzie and George Brown. And he built plennnnty more than that, too.

Of course, due to people sometimes being stupid, the General Post Office was torn down. That was in 1958, as Toronto was swept by a short-sighted orgy of modernism. It was replaced by the nondescript glass office tower that stands boringly at the head of Toronto Street today.

And it's not alone. The two blocks of Toronto Street, between Adelaide and King, were once two of the most gorgeous blocks in the entire city. But now, just about all of the old buildings you can see in the photo below have been demolished and replaced. One of the few survivors is the impressive columned building on the very left – which just so happens to have been Toronto's seventh General Post Office.

And it's not alone. The two blocks of Toronto Street, between Adelaide and King, were once two of the most gorgeous blocks in the entire city. But now, just about all of the old buildings you can see in the photo below have been demolished and replaced. One of the few survivors is the impressive columned building on the very left – which just so happens to have been Toronto's seventh General Post Office.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)